News

A Kentucky-Based Introduction to Golf Course Architecture

You go play a golf course for the first time that you have not previously seen. After the round, your friends and family ask you, “Did you like the course?” The answer is either yes or no, but what goes into your decision-making process? Is it the condition of the golf course? The friendliness of the staff? Whether you recorded a good score or not? How often do you consider the architecture and design of the golf course? The course’s layout is the only one of these possibilities that dates back well before you stepped foot on the facility’s property that day. Golf course conditioning, customer service and your play can vary day-to-day. If you go play somewhere like Owensboro Country Club, nine of those holes were originally laid out a century ago in 1919 while the other nine came along in the 1940s. Even though renovations have been made over time, the choices of an architect from one-hundred years ago will play a role in your experience.

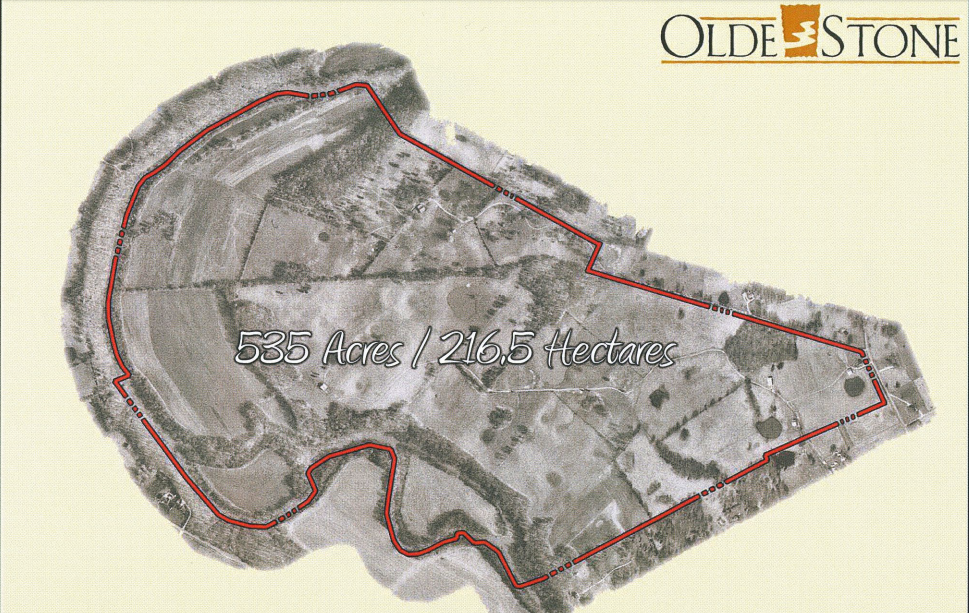

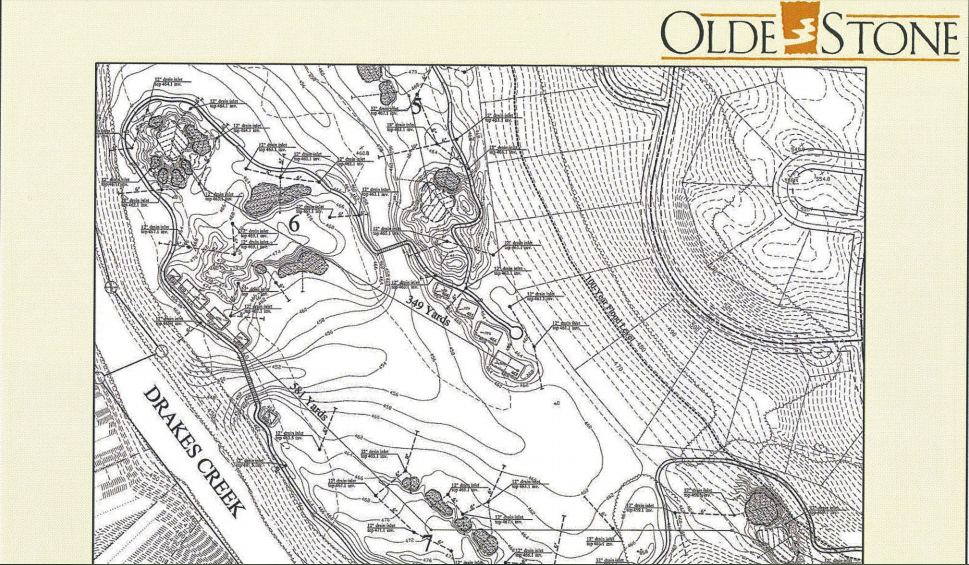

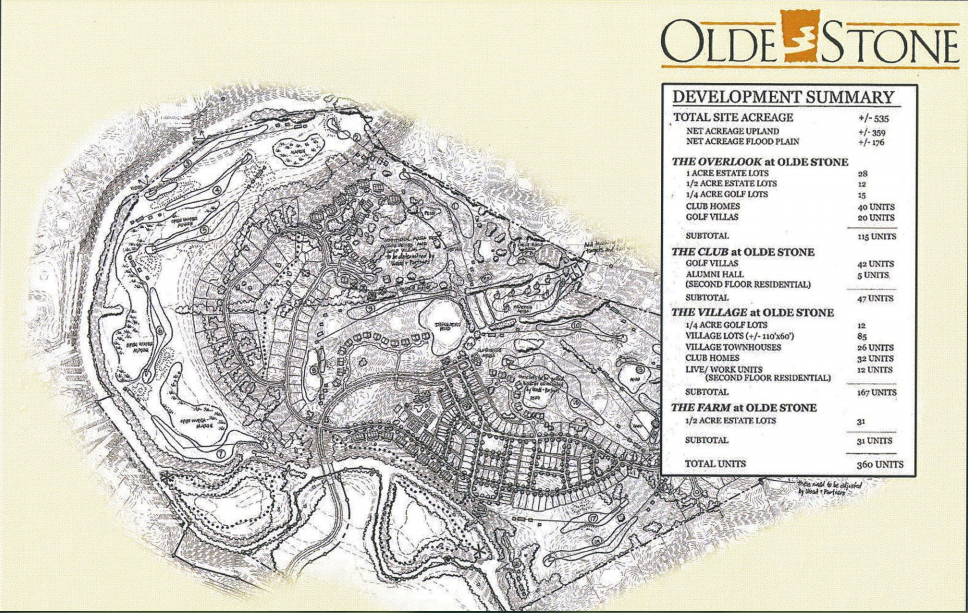

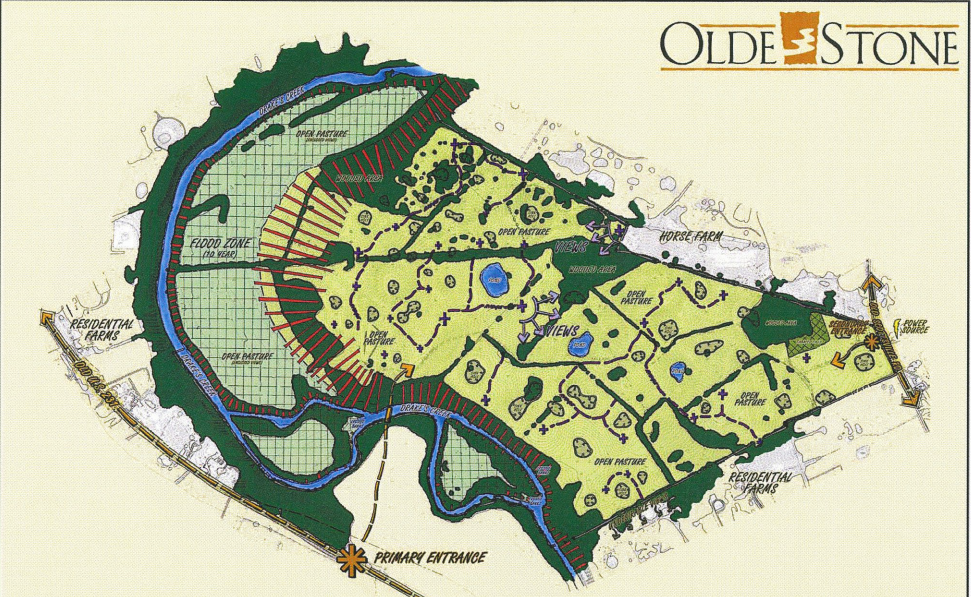

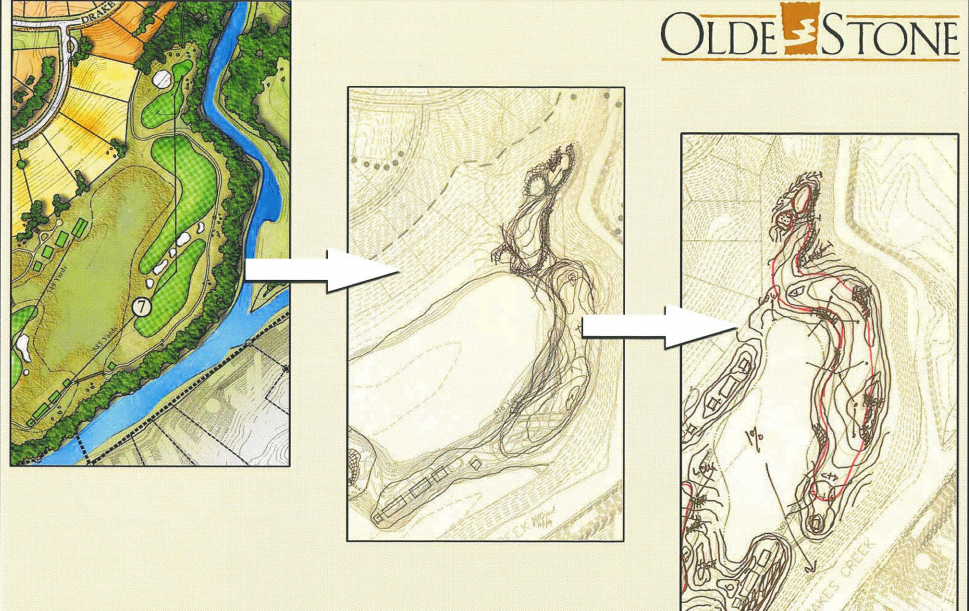

Recently, we received the opportunity to speak with Steve Forrest who has worked closely with Arthur Hills through the years. If Arthur Hills’ name sounds familiar, it would be because he led the design of three of Kentucky’s most well-known venues: The Club at Olde Stone, Persimmon Ridge Golf Club and Keene Trace Golf Club (Champions Trace). Unfortunately, Hills is not in the greatest health at the moment, but Forrest was extremely generous with his time to answer many questions about what golf course architecture entails. A Q&A follows which provides a wonderful synopsis on portions of the process. Topography maps of Olde Stone, which Forrest mentions multiple times as a critical asset to an architect, will follow to provide an example of what those look like.

…

How did the process work to become a course’s architect in the 1900s? Did the facility’s founders contact an architect or would an architect reach out to prospective clients?

More often than not, the golf course client would reach out to the architect. It would be hard to know what new golf courses were coming along in those days. Being a golf course architect and growing your career is one big snowball effect; once you get your name out there, people start learning your name, experiencing your work and begin to figure out which architects they want to have design a course.

How much has that process changed over time to present day?

It’s certainly changed in that things are more renovation-driven ever since the 2008 recession. We reach out to clients about if they have any interest in updating their course and bringing it to modern standard. With the amount of new golf courses in the U.S. being built dropping off significantly from what the numbers were in the 90s and early 2000s, renovations are the bulk of our modern work.

The first times you or Arthur step foot on a prospective facility, what are you all looking for in the property and what do you want to know about it?

We quickly ask for a topography map and the property boundaries so we have a better understanding of the overall scale. Persimmon Ridge was so wooded that the topography map lets us see the land that is there even if you cannot see it from the naked eye, which was the case on hole 3 for instance. So the topography map is critical and we draft a conceptual routing of the overall layout before we make our first site visit so that we can test it upon our visit. The owner might have a preferred clubhouse location in advance, but you’re working with lots of different puzzle pieces between golf course, practice facility, parking lot, clubhouse, and many other things to get everything to mesh well in the end.

What kind of specific challenges did you guys encounter when building Keene Trace, Persimmon Ridge or Olde Stone? Outside of the state, what can be difficult to work through?

Environmental regulations have gotten stricter over time. The primary ideas that need to be respected are wetland areas, tree restrictions and floodplains. With Olde Stone, we needed to respect the flow characteristics of the water to get tees, greens and fairways above the flood level for a majority of the front nine since that area can flood easily. Persimmon Ridge was most importantly going to be a golf course with housing coming in second. Keene Trace actually turned out to be the same way. Residential areas fortunately did not drive the designs in Kentucky like they so often do when we have projects in retirement communities in Florida.

How many options of various routings were there for Keene Trace, Persimmon Ridge and Olde Stone? Was it cut and dry which eighteen holes you would build or were there dozens of options for holes?

On some courses we just do one routing which is the one that ends up working which is the category these courses fell under. Other courses we’ve built have had about fifteen different master plans. We meet with the engineer and owner to go over everything which can take two days to figure out what works and what will end up being built. Sometimes these conversations can be as specific as twenty-foot differences as far as making an area safer or just that much more playable.

Does the facility’s client indicate how hard they want the golf course to be or do they leave that in the hands of the architect?

We typically get some amount of guidance on this subject from the client. Ultimately, you can bet on a wide level of skills playing a course unless it will be something like a men’s club. The old expression of wanting the course to be as challenging as you want from the back tees while simultaneously being as fun and playable as possible from the forward tees really is the mission. In Florida, some of our golf courses need to have upwards of seven different tees so that the golf course is playable for those that are aging and cannot hit the ball very far anymore.

Bluntly, what defines a good hole and what defines a bad hole?

A good hole gives players options. You can stand on the tee and see where your target is. We want the golfer to say to themselves, “If I can carry that bunker, I’ll be thirty yards closer to the green. If I don’t cross that water, I’ve got a longer approach coming in.” Obviously the more beautiful and aesthetically pleasing the hole is, the better. A bad hole gives you little idea what’s happening off the tee. You don’t know where you’re going. A forced layup or forced carry is never great either because it becomes impossible for the high handicap golfer to play without getting overly frustrated. Many times, we design the green complex first and work backwards so that the angles hitting into the green are well-known to us. That correlates to good shots being properly rewarded without unfairly penalizing a quality shot.

Of the Kentucky courses your team built, is there one that was more naturally blessed for golf along with one that required more man-made construction in order to be fit for play?

These are actually three of the more similar sites we’ve done in a given state. Each of them didn’t require as much earth-moving as other projects we’ve worked on. We were very blessed to be able to work with these properties. Kentucky is a beautiful state filled with rolling hills so the topography map on each facility was very handy so we could see what elevated tees might work well and what green complexes would fit the layout. Of the three in Kentucky, Olde Stone was probably the most difficult to build because of the floodplain we had to take into consideration.

How often do you all keep in contact with the facility after the construction of the golf course is finished?

It’s to our advantage to reach out as often as possible. It used to be between two to three years without reaching out excluding Merry Christmas wishes or things like that. But given the fact this is a renovation-based era, keeping tabs on how the golf course is being received translates to good business. This past summer we actually delivered the original paper plans of our Kentucky golf courses to the facilities so they could have them. Having those paper plans isn’t as common anymore now that most things are done digitally, but it’s a fun thing to do to reconnect with past clients and maintain a quality business relation. Each project we do is special and unique to itself.

If the golf course’s players are highly critical about a design, how does that affect any architect and does it propel them to want another crack at its building?

It certainly doesn’t make us want to change things right away because we know the full story between tree removal, wetland restrictions and other factors like those. You have to be thick-skinned in this business so you can shake off criticism, while also keeping in mind the players don’t have the full understanding of how the construction went down. Unless a client brings an issue to us that is urgently destructive or problematic, we never overreact to criticism.

Worldwide, what does Arthur consider to be his finest work?

Arthur’s standard answer is “Which child or grandchild do you love the most?” We’ve had wonderful opportunities throughout our careers and the Persimmon Ridge project with Elmore Just leading the way was one of the most amazing experiences we’ve had. Each project we do is special and unique to itself and we love each course we design for different reasons.

What is a course you’ve drawn inspiration from or an architect you’ve looked up to?

Arthur would answer this differently than I would since we’re in a different generation, but he has a lot of love for Seth Raynor and Donald Ross, the classic architects. I’ve been influenced by Pete Dye and frankly Arthur was too. He’s a master of strategy and I’ve always admired his philosophy and ability to be bold for a long time. Many of his courses have had an impact on how I design a course.

What’s something about golf course architecture from behind the scenes that people don’t know of that would surprise them?

The amount of revisions we make during the construction process, especially over matters most people would consider to be minor. Small things like the horizon not lining up with a green complex would be an example. Some architects can be demanding of a green needing to be moved just fifty feet or so because otherwise it won’t have the flexibility the architect wants. We rarely encounter that issue as being able to understand a topographical map means you can finely pinpoint where you want everything to be, knowing it will work as you envision.

…

Golf course architecture is purely subjective. What one person likes may not be another person’s cup of tea. Therein lies the beauty of the process. With only very few exceptions, no golf course yields universal praise. Not everyone loves the Old Course at St. Andrew’s. Augusta National and Pebble Beach are trending downward in terms of their place among the world’s best. What fits one person’s eye may be an eyesore to somebody else. What can be generally agreed upon, as Forrest alluded to, is that the key to an architecturally good hole is the amount of strategy the player must utilize to have a successful score.

The best golf courses to play and to watch tournament golf on are those that provide the player options. Holes that require players to hit only one type of shot or fail to make the golfer consider hitting any club other than driver off the tee get boring and limit a good golfer from being able to separate themselves from the average golfer. The holes that force a scratch golfer to carefully consider what they want to do while also being playable for the bogey golfer are the ones that should be celebrated, because they keep the game interesting but fair.

As an example, let’s examine a hole in Kentucky that many people have played and have experience with: the par-four 16th at Kearney Hill in Lexington. This is a Pete Dye design that has hosted many nationwide championships for good reason. What the 16th does well is force players before their tee shot to make a decision on how aggressive they want to be. Essentially, the player has four options, which are displayed below.

Option A: This is the boldest play that can offer the biggest disaster while simultaneously eliciting a good birdie chance if played correctly. The golfer takes out driver and must take on a majority of the large pond left of the fairway to leave themselves with the best angle into the green. By pulling it off, a shot from inside one-hundred yards remains with the water mostly out of play at this point and the trees a non-factor.

Option B: Speaking of those trees, this option is the bail-out shot if you hit driver off the tee. The chances of finding the water off the tee drops substantially by taking this play, but your second shot becomes rather challenging. The golfer would either have to hoist a wedge way up in the air to fly the trees or hit a punch shot underneath the trees. By hitting a punch, the water comes back into play because a shot with too much steam or one that begins to hook will find a watery grave.

Option C: This is a blend of being both aggressive and conservative. Hitting a long iron or mid-iron will find this area in which you challenge the water off the tee and get rewarded by not having to mess around with the trees on your approach. Since you would be hitting a mid-iron or short iron into the green with your approach, the water still comes into play with your second shot as the chances of pulling or hooking a shot (for a right-hander) gradually increases the farther away from the green you are.

Option D: The play to make if you absolutely refuse to find the water off the tee. Take out an iron, aim for the right side of the fairway and make it at least one more shot without having to worry about taking a drop. The problem is your second shot becomes incredibly daunting. Not only do you need to fly the trees, but your margin of error for missing left is nonexistent from this angle. This shot is arguably scarier than the tee shot and can lead to a surplus of issues if played incorrectly.

Let’s keep in mind this is one of the shortest par-fours at Kearney Hill but is far from an easy birdie unless you hit the shots Dye demands you to. Geoff Ogilvy, the 2006 U.S Open champion, once said on a Fried Egg podcast that “the best holes offer the slimmest margin between birdie and bogey.” A golfer can hit two average shots and two-putt for par on many holes without really thinking about it. When the player needs to execute a shot that has danger surrounding it but can be properly rewarded, a proper test of golf has been identified. The 16th at Kearney Hill fits the bill.

…

The aforementioned Fried Egg is a phenomenal destination to expand on your golf course architecture knowledge. Among the variety of articles they have dedicated to developing a person’s knowledge with golf course design are their discussions on template holes. These are some of the most popular holes among both architects and players, hence why they are given the “template” moniker. These holes originate primarily from the golden age of golf course architecture that was led by architects such as Seth Raynor, Donald Ross, C.B. McDonald and Alister MacKenzie among others. Template holes consist of the biarritz, the redan and the cape just to name a few.

Kentucky was unfortunately missed by many of the architects who worked in this timeframe, but template holes have stretched throughout time and been duplicated by many architects because they work so well. The Commonwealth has been fortunate to have some of these built within its lines, such as the 16th at Kearney Hill that was documented. So even though you may not have realized it, there are probably dozens of holes you have played that drew inspiration from a template hole. Many architects have expressed this notion in the past, but it has proven very difficult to create new holes that are uniquely great. Most holes that are applauded are copied from other holes that architects have seen over time. Not that anyone minds, as fun and interesting holes like these will hardly ever become tiresome.

Without the work of architects, none of us would be able to enjoy golf. It can be taken for granted how much hard work and effort goes into providing a worthy creation for people to play, but the creativity and imagination of golf course architects are the building blocks for some of golfers’ best memories. The next time you check out a new facility you have not previously seen, keep some of these ideas in mind to develop a well-rounded opinion of the golf course at hand.