News

A Bounty of Blessings for Bobby Nichols

By Bob Denney

Editor’s Note: In celebration of its centennial, the Kentucky PGA Section pays tribute to Louisville native Bobby Nichols for his historic triumph over 60 years ago that made him the state’s first major golf champion. The following appeared in the 2014 PGA Championship Journal.

Half a century has passed since Bobby Nichols stunned the golf world with a record-breaking performance in the 1964 PGA Championship. Today, he can reflect upon a journey that also has been a charmed life. Twice he stepped over and through portals of near tragedy and went on to leave an impact upon many lives.

A dozen years before he walked the fairways of Columbus (Ohio) Country Club to close out his lone major championship victory, Nichols was a 16-year-old standout basketball and football player and golfer at St. Xavier High School in Louisville. On September 3, 1952, he was one of five teenagers on a joyride on the outskirts of the city. Nichols was riding in the front passenger seat and a friend was driving more than 100 mph when the car failed to make a curve, spinning out of control. Flung through the windshield, Nichols was the lone passenger who didn’t walk away from the scene.

He received the Last Rites of the Catholic Church before doctors realized that he had a pulse. He lay unconscious for 13 days, paralyzed from the waist down, having sustained a broken pelvis, twisted back, collapsed lung, an injured kidney, and a concussion. When he awakened, his sisters, Joyce, and Catherine, were by his side. Bobby muttered, “Did I miss football practice?”

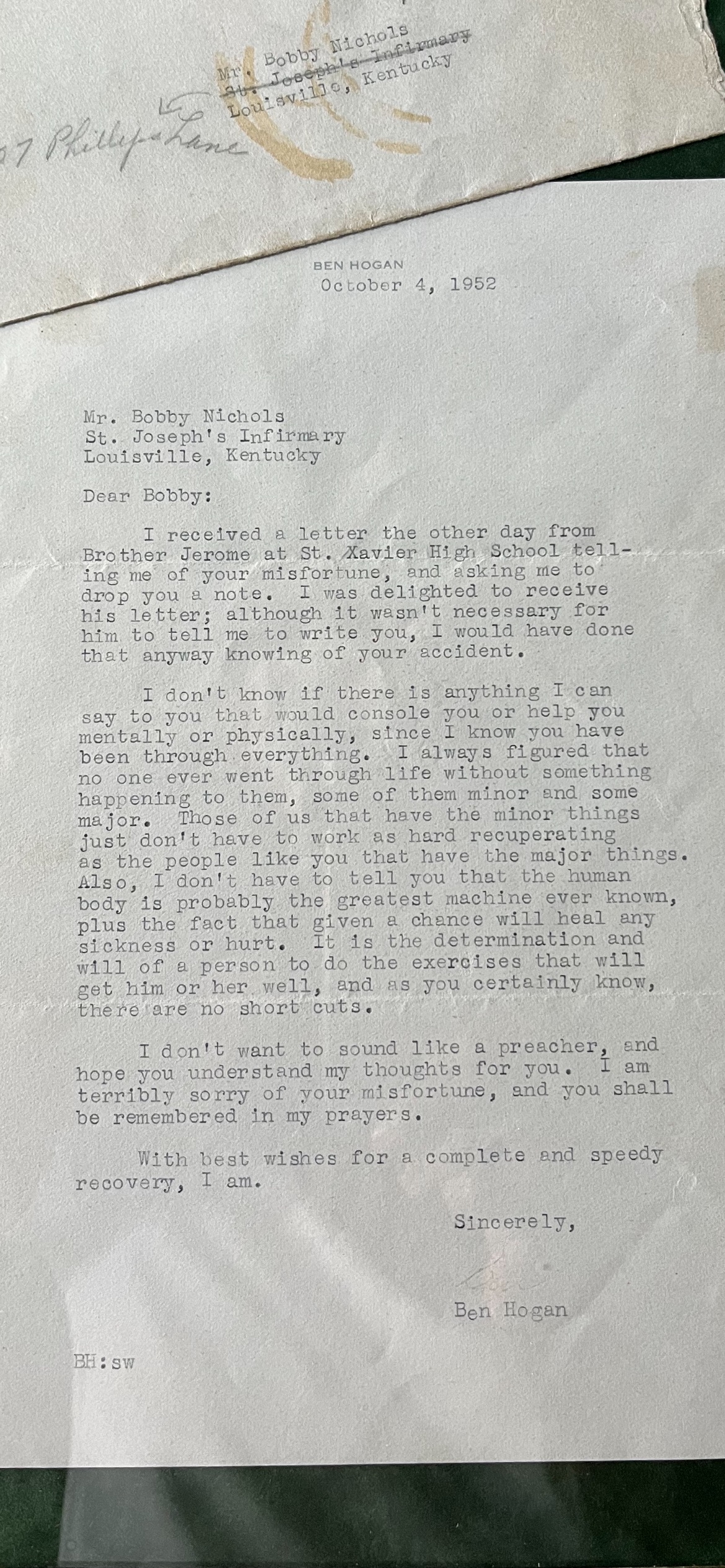

The paralysis faded away after two weeks, but Nichols spent 96 days in the hospital. A teacher at St. Xavier, knowing that Nichols’ football and basketball days were over, contacted Ben Hogan, who came back after similar injuries from a horrific crash in 1949. Hogan sent a note of comfort.

“Hogan wrote me a letter that helped tremendously. I still have it framed,” recalls Nichols, now 78. Hogan and Nichols would cross paths often over the next 20 years, but not before St. Xavier football coach Johnny Meihaus, who had played for Bear Bryant at the University of Kentucky, intervened.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Meihaus asked if Bryant, who in 1954 took the head coach and athletic director posts at Texas A&M, would give Nichols a scholarship even though he knew the young man would never play football.

Nichols received the scholarship and was later called into Bryant’s office, where the legendary coach said, “I’d like you to come out regularly and talk to the boys.” Nichols went on to play on the golf team and repaid the favor to Bryant by winning the 1956 Southwestern Conference Championship. In later years, Nichols and Bryant were frequent partners in the pro-ams.

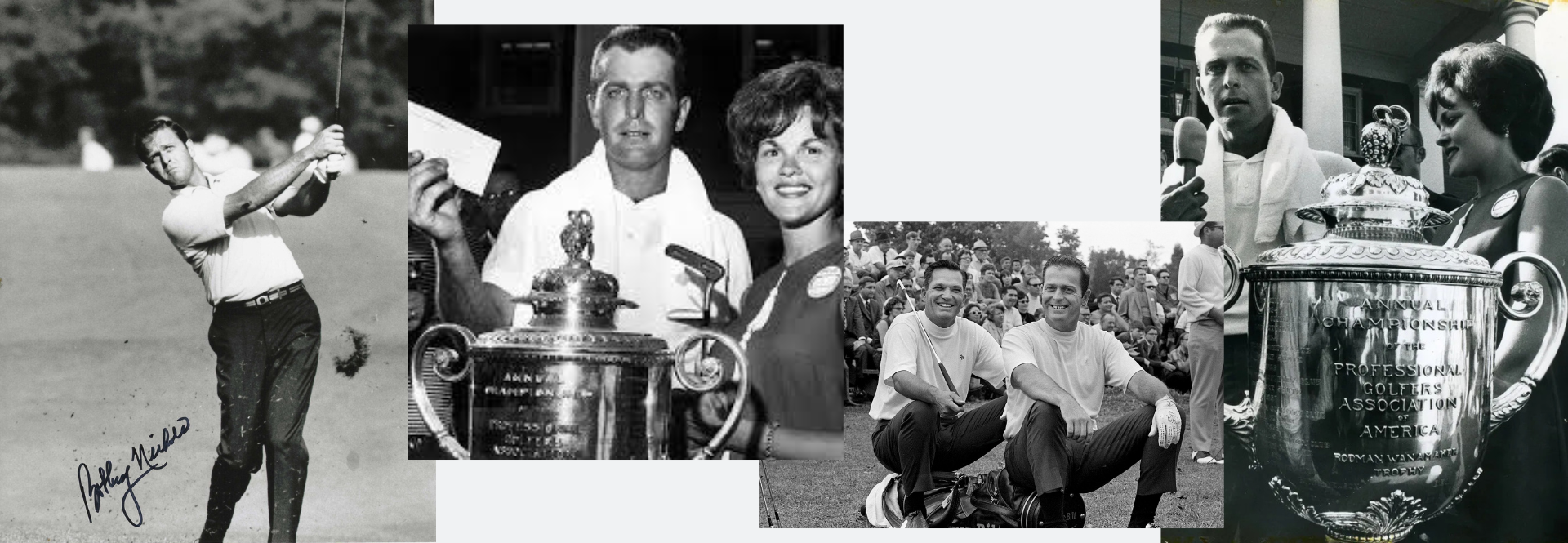

Nichols turned professional in 1960, won 12 times on the PGA Tour and captured one title on the Champions Tour (today’s PGA Tour Champions).

During a humid, 90-degree week in July 1964 at Columbus Country Club, Nichols earned his signature golf achievement. Facing a PGA Championship field boasting 31 past or future major champions, Nichols arrived with a second-hand brass blade putter he bought for $5 from a golf shop at Owl Creek Country Club in Anchorage, Kentucky. A disillusioned member had put it up for sale.

That putter, which Nichols kept and won with seven times, became his magic wand.

Opening the PGA Championship with a 64, Nichols cruised along for 63 holes before he found himself standing in the 10th fairway of the final round, tied for the lead. That day, Nichols was paired with Hogan.

One group ahead, Arnold Palmer had rallied for a share of the lead along with a hard-charging Mason Rudolph. Nichols faced a second shot to the 528-yard, par-5 over a small ravine to a flagstick tucked behind a greenside bunker.

Nichols reached for his PowerBilt 3-wood and launched a rocket of an approach shot that settled 35 feet from the hole. Nichols then stroked home the eagle putt.

“I knew I had to win when that eagle went down on No. 10,” says Nichols.

Although struggling off the tee, Nichols was at ease on the greens. He birdied from 15 fee at the 15th hole, saved par from 18 feet at 16, and drained a 51-footer for birdie at the 17th for a four-stroke cushion over Palmer.

“After I holed that long putt, there was Mr. Hogan with a bit of a smile on his face,” Nichols recalled. “He looked at me, shook his head, and then had to smile again.”

After the round, Nichols recalled Hogan’s only comment. “I was surprised that you went for the green at 10.”

“I felt somebody was watching over me in this one,” Nichols said afterward. “I felt from the first day that if I was ever going to win a major championship, this was going to be it.”

The wire-to-wire victory and 72-hole total of 9-under-par 271 would be records that stood for 30 years, until Nick Price broke the Championship record with a 269 total in 1994.

“Winning the PGA Championship was a real plus for my career,” says Nichols. “I won a lifetime exemption into the Championship, and some perks.”

In 1967, Nichols was hired as PGA Head Professional at Firestone Country Club in Akron, Ohio, where he remained until 1980.

It was during this period that Nichols survived yet another disaster. He was one of three players, including Lee Trevino and Jerry Heard, who were struck by lightning during the second round of the 1975 Western Open at Butler National Golf Club, near Chicago. All three lived, but with varying physical effects.

“I spent 48 hours in the hospital as they monitored my heart,” Nichols recalled. “That was before lightning detection devices came into tournaments. That incident really started the practice. It’s done a lot of good and saved a lot of people.”

Nichols surviving a double brush with mortality resulted in a large number of folks in this country being better off today. They include members of the Wounded Warriors Project; countless schoolchildren benefiting from Blessings in a Backpack, which was founded in Kentucky in 2005; and the Bobby Nichols Fiddlesticks Charity Foundation of Fort Myers, which began in 2003 and has raised more than $5.4 million to aid abused and neglected children in Southwest Florida.

[Note: Through 2024, the Nichols Fiddlesticks Charity Foundation, and the Nichols Cup tournaments and auction gala has raised more than $18 million to benefit local children’s charities.]

Back in his hometown of Louisville, there are two enduring reminders of the major champion in Waverly Park, on the city’s southwest side, the Bobby Nichols Golf Course welcomes golfers to a nine-hole layout. Twenty minutes northeast, at Bellarmine University (formerly Ursuline College), where his sister, Joyce, once studied to be a nun, there rests perhaps the most significant Nichols “marker.”

Never losing sight of his faith, Nichols, who attended Mass daily while he was on Tour, donated a portion of his $18,000 first-place PGA Championship check to erect a statue of St. Jude, the patron saint of desperate and lost causes.

Bob Denney is Historian Emeritus of the PGA of America